Globalization is a synonym for global economic integration. Globalization is an accelerated process of pumping in capital, production and markets and extending them to all areas of biosphere with the aim of increasing profit margins. Emerging market economies (EME’s) have become much more integrated into the global economy over the last five decades along numerous magnitudes. But the trade war and the pandemic have unquestionably invited deglobalization. It has become a commonplace to say globalization is at crossroads and this is not the first wave.

The world was at this junction even before the virus entered our lives. It has been a linear progression from the global financial crisis of 2008-09 to the great populist movement in 2016 and the US-China “decoupling” – these events have taken over a course with the virus being the victim for deglobalization.

The pandemic has made it clear that we rely way too much on the global supply chains and has made us realise that these chains are vulnerable and in due course unsustainable. Now there’s a rush to reorganise the chains to reduce interdependence as alliances are uncertain and international cooperation seems absent. The demand for protectionism and self-reliance is mounting.

Many governments in emerging economies have sought to foreign direct investment. This helps lift productivity directly by increasing the efficiency of the acquired firm and indirectly by diffusing technology to local competitors and suppliers. In element, there is also a decline in FDI. We also see a financial decoupling.

Now, how do you assess cascading sequences of the drop in profit margins?

Profit basically represents the difference between revenue and cost and have significant role to play in assessing a company, economy, and business cycles. Profit margins also play a role in changing corporate behaviour, as margins effect investment decisions and hiring decisions. Expanding profit margins correlate with expansion in the economy. Expansion will mean more hiring.

And higher margins create a backdrop for CAPEX and R&D investment that result in higher levels of margins. Increased profits cause the stock prices to rise as it depicts the future of the company and resulting in issuance of dividend or stock buybacks.

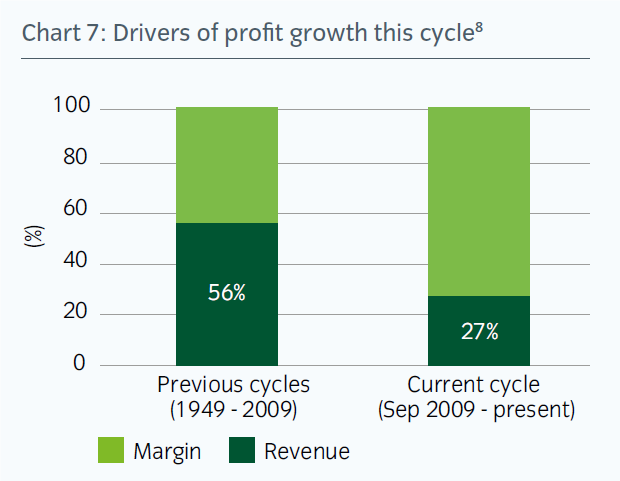

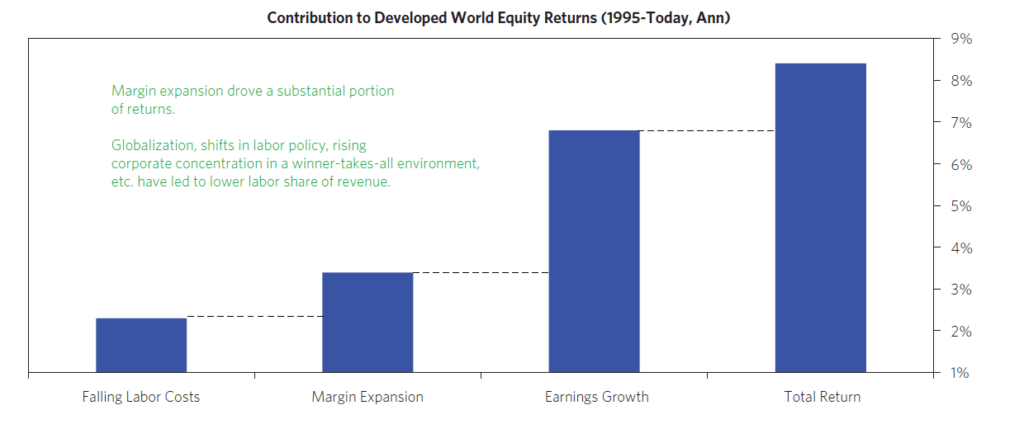

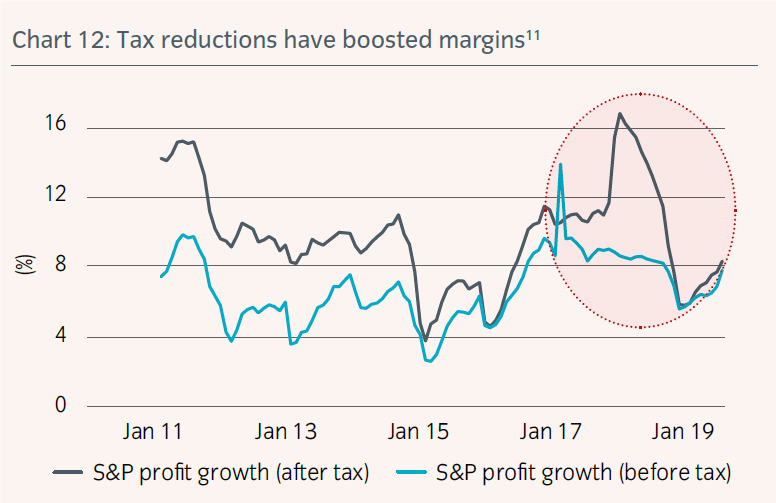

There has been a consistent rise in US corporate profit margins since the global financial crisis of 2008 and falling margins are seen as a precursor for recessions and act as an early indicator. The margins of companies also coincide with business cycles and accelerate in recovery phases peaking during mid cycle. The dip in profit margins is also depended on the severity of the economic fall down. As we can see the fall in margins is lower in 2001 compared to 2008. The record high margins was witnessed in 2018, after the US corporate tax policy changed but have eroded in the wake the trade war. However, according to J.P. Morgan, profit margins accounted for half of EPS growth since 2001.

Many borderline proxies supported this expansion of profit margins. According to Bridgewater’s report corporations have benefited from declining labour bargaining power, increased globalization, lower anti-trust enforcement especially in the US, technological advances enhancing scalability and pushing down marginal cost, lower interest rates and corporate taxes. The combination of these factors have resulted in enhanced and business friendly environment, especially in America.

Let’s see them in detail below –

• Tumbling labour Cost

The dwindling labour cost is one of the most important factors that contributed to the expansion of global profit margins. This dramatic fall in cost of labour is due to cheaper access to foreign labour particularly in Asia. Globalization weekend the bargaining power of labour due to the increase in automation of production. While globalization has boosted overall welfare, the benefits have been unevenly spread. Corporate lobbying gained political power and have shifted the policies in their favour. In fact, the challenge for policymakers is how to reduce the adjustment costs and narrow the gap of the reallocation of labour- and capital-intensive sectors.

From 1980 to 2013, global corporate after-tax profits grew 30% faster than the global GDP. Along with that corporate net income grew more than 50% faster than global GDP. Real beneficiaries of this phenomenon have been the North American and European counterparts as they have driven the trend of globalization and they have been rewarded handsomely as well with Bridgewater estimating that rising corporate profits have accounted for over half of developed world equity returns for over past 20 years.

The dependency on China has been astronomical given the robust labour market and China now contributes 28% of global manufacturing (2018). Corporations with flexible labour laws have benefited disproportionately as they have been more successful in expanding profit margins.

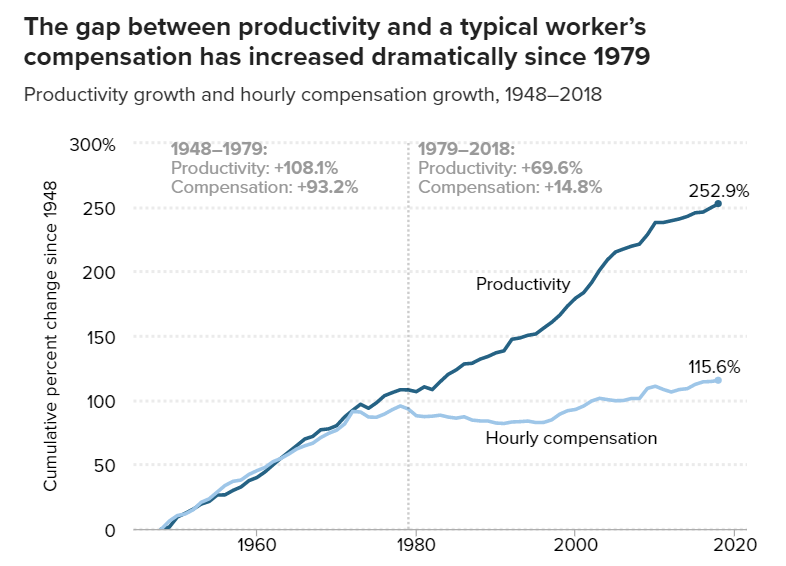

Corporations in the US have also benefited from large population of China and India coming online. And the productivity factor in the US has expanded from 1979 – 2018 with a 69.6% increase whereas US hourly wage has only seen a rise of 14.8% during this period. The five-fold productivity rise has had substantial positive outcome on profit margins. This is how highly the labour cost is changing the game of profits.

• Increased Globalization as a cornerstone of international economics

The increased globalization extends well beyond the flow of cross border trades, data, technology, and investments perhaps it also includes the flow of workers, students and tourists.

Over the years manufacturing shifted from the developed nations to Asia and majorly to China resulting in exponential increase in profits. This was possible only due to declining trade barriers and developments in communication and transportation technologies which have allowed firms to split up production processes into various stages and locate them around the world to exploit differences in factor endowments and comparative edge. However, these profits were marginally passed on to customers as lower prices for longer periods. Although in most cases these higher margins were retained by the companies themselves.

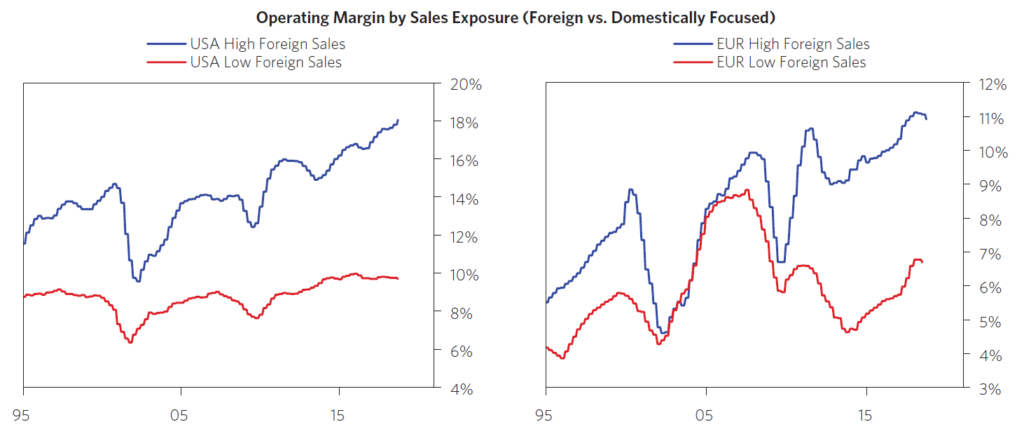

This exposure is very evident when looking at the difference in margins of companies with high foreign sales compared to those with low foreign sales. The discrepancy was large across products with computers, electrical equipment, and machinery seeing a large increase in margins as these could be manufactured in China, whereas utilities and construction material saw low margin expansion.

• Relaxation of Anti-Trust enforcement

Since 1970s we have seen a consistent decline in antitrust enforcement in general and even more so in America. The range of conduct that would ordinarily be condemned as antitrust and anticompetitive has decreased significantly. And over the years it has been more difficult to prove that companies are indulged in anticompetitive behaviour. Less anticompetitive behaviours are beneficial for the customers, as customers get the benefit of lower price, better quality and more competition also leads to more innovation which further creates more jobs and decreases inequality in the society.

Although, the number of merger fillings have increased 44% from 2010 to 2018, the number of enforcements have remained low and steady. In 2018, 2028 mergers fillings were reported and mere 39 of them were flagged. Coupled with U.S non merger actions being at historic low.

The lower anti-trust enforcements have helped the firms to have greater pricing power. A greater pricing power is derived from higher economies of scale, lower competition in the markets and higher bargaining power over labour and suppliers.

What explains the current trade slowdown?

• “Slowbalisation”

It means continued global integration but albeit at a significantly slower pace given the slow trade growth, tighter immigration policies and the increased protectionism measures. As per PwC predictions slowbalisation is the new globalization.

Before discussing deglobalization, lets discuss the major factors contributing to expanding global trade. The real boost in globalization was seen after 1990, after China and India rebounded and entered the global markets and abandoned autarky. European Union was formed, and shipping cost went down. America, Mexico, and Canada signed NAFTA. And in general, the WTO supported tariff cuts.

However, everything is not roses anymore. Global trade was witnessing a slowdown before Covid-19. According to The Economist, global trade has fallen to 58% in 2018 from 61% in 2008. Cross border FDI dropped from 3.5% of world GDP in 2007 to 1.3% in 2018. Cross-border bank loans declined from 60% of GDP to 36%.

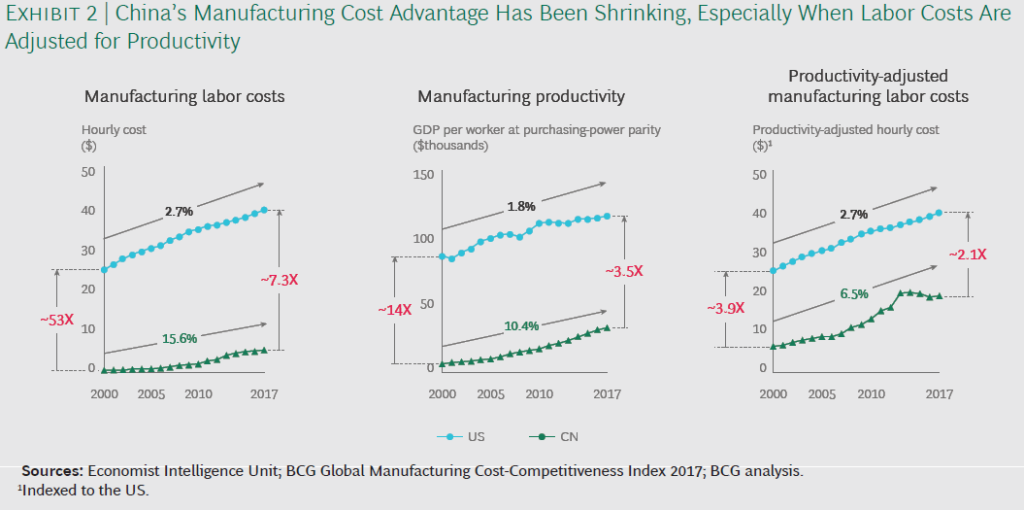

The China factor of globalization is also declining, previously China was considered as a country with inexhaustible labour, but not any longer with costs rising in China. In the year 2000, Chinese manufacturing labour cost averaged only 46% per hour, 53% lower than US wage of $25. However, rise in Chinese manufacturing costs at 15.6% p.a. has outpaced the rise in productivity which was just 10.4% p.a.

According to BSG’s global manufacturing index, in 2016 productivity adjusted manufacturing cost in China came close to Southern America for some industries. However, China is still extremely cost competitive for a wide variety of products, such as semiconductors, IT hardware and Chemicals.

• The US China “decoupling”

Arguably, this trade war has been a landmark event for deglobalization. In fact, global trade has been declining since 2018 both in value and volume with considerable disruptions to the global supply chain.

The Coronavirus has collapsed demand and production in many industrialized economies and the divestment from developing countries will have more long-lasting effects on global supply chains than the temporary supply chain disruptions. Gartner Research found that in a survey of 260 global supply chain leaders, 33% had already moved or plan to move manufacturing out of China in the mere future. The tariffs induced an additional cost of 10% for more than 40% of these organizations. However, despite the cost increase, companies want to move away from China and make their supply chains more resilient. 58% of the respondents on the survey respondents, agreed that more resilience will bring more structural cost, which will ultimately come at a cost both to the firms and customers.

• Taxes

In 2018, trump administration decreased the corporate tax rate from 35 to 21% making a pro-corporate move this resulted in margin expansion for every firm and margins increased exponentially. However, soon after Trump’s engagement in trade wars, those exponential margins were washed away.

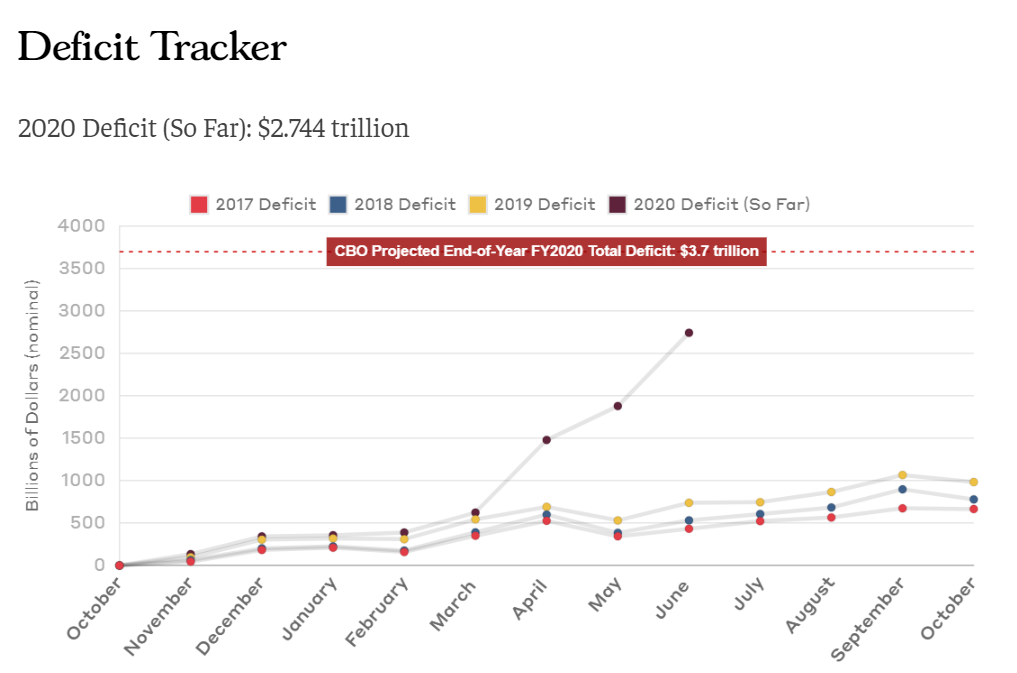

However, in the wake of coronavirus the taxes may not stay at 21% anymore and we may see an increased tax rate in the medium to long run. America was already running a $984 billion deficit in 2019, which was considered unusually a large. However, that figure has blown out of proportion on the back of relief measures being extended during the Covid-19 pandemic. The current fiscal deficit has reached an astronomical number of $2.744 trillion (June 2020) with more on the way. And corporations shall most likely be the ones paying for it in the form of contracting margins.

Preparedness by companies:

Covid has already acted as a stress test for some companies as no one ever expected a total shutdown of the global economy. However, we might see more and more firms struggle as we start contracting margins. As companies with the likes of majority of the airlines in the US and even high-profile companies such as IBM have bought back stock at a tremendous pace rather than investing them in future R&D or other income generating assets.

If these companies used that cash in hand, to invest in R&D and income producing assets they would have made a return on it rather than just short-term gains of increased EPS.

Instead of putting the money into productive projects, these companies have distorted their position in the market as well as the future of the company. And in the case of IBM, which was one of the most innovative companies of the 90s, is just a fallen angel when compared to Amazon or even the big tech. Just for reference IBM has bought back $83 billion in stock since 2009 and has a current valuation of $109 billion.

On the contrary, instead of giving dividends or buybacks, Amazon invests in growth, they use that cash to come into a new industry and disrupt and gain a position or do massive R&D spends that no other company can undertake except them. Whereas, IBM has used that money to just buy back stock instead to investing it in income producing asset or R&D and we can see for ourselves that they have struggled.

These buybacks have caused to the markets to boom and have delivered an average return of 11% from 2011 to 2019. However, the growth has not been fuelled by earnings growth. A major part of this EPS growth has come from buybacks. Here, are two facts about the buybacks:

i. As of August 2019, US Corporate buybacks have returned $5 trillion to shareholders since 2009.

ii. In the US over the past five years, corporate share purchases have boosted EPS growth by 1.7% per annum.

Buybacks disproportionately benefit the management and sellers of the stock. For the management it helps management to reach EPS growth target by reducing the number of shares in the company.

Where do Revenues and Costs go from here?

Profit margin is the function of both revenue and cost. We need to take in account both the proxies when projecting where the margins will go. In the recent turn of events its safe to assume that top line growth for the mainstreet will be muted. The disruptions caused by the pandemic and the very evident trade imbalances will drive the top line to go down and the cost to go up. This virus has bought a new wave of nationalism in the world with industries moving back to their home countries as seen with Japan, India, and the US.

The hopes of a v-shaped recovery on the mainstreet have been false with the entire world economy contracting at -4.9% in 2020. Slow trade has put a substantial pressure on future investments as well, it very much looks that we will see slow recovery even after the vaccine. The companies that enjoyed high profit margins over the years will face pressure as various strong proxies become a drag on these margins.

A Special Mention to Pooja Kundan. Thank you for your contribution!

Follow Us @

Some Unrelated Stories!