Everyone who has played the game of monopoly would be familiar with the fact that a huge part of the game is Negotiating! Also, the disappointment that you are met with when the player who owns the coveted Dark Blue properties (a.k.a Mayfair and Park Lane in the UK edition and Boardwalk and Park Place in the US edition) would not part with it in exchange for any deal that you believe is the best that you can offer, makes you envious of the bargaining power that the player holds. I had to endure exactly that on each of our Monopoly game nights as I never managed to get myself on the winning side of the negotiation.

Last weekend, as I sat next to the winner with the Dark Blue property, sulking over my failed attempts at negotiating good deals in the game, I was reminded of yet another spectacle of a successful negotiation when India pulled out of the China-backed mega Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) over unresolved “core concerns”, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi stating in Bangkok that the proposed deal would have adverse impact on the livelihoods of all Indians. After all, a no deal is better than a bad deal!

Prime Minister Narendra Modi aptly applied this quote from Robert Tew which read “Respect yourself enough to walk away from anything that no longer serves you, grows you, or makes you happy”.

So, why was the RCEP synonymous to winning a monopoly deal? How did India win the coveted Dark Blue property (or did it already have one)? Why was India not ready to trade its priced possession with the other players? Here are some thoughts that are worth reflecting upon.

What is the RCEP?

Beginning with what the RCEP agreement is, it attempts to establish the world’s largest free trade bloc comprising of 16 countries. A free trade agreement (‘FTA’) would essentially mean an integrated market with 16 countries, making it easier for products and services of each of these countries to be available across this region.

In modern international trade, few FTA’s result in completely free trade. Governments with free-trade policies or agreements in place do not necessarily abandon all control of imports and exports or eliminate all protectionist policies.

The negotiations that were going on between these countries since the last 7 years were focused on the following: Trade in goods and services, investments, intellectual property, dispute settlement, e-commerce, small and medium enterprises, and economic cooperation.

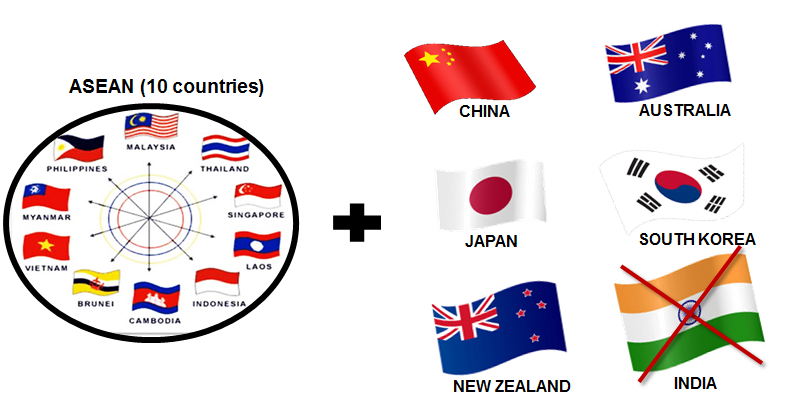

The countries in RCEP include the 10 ASEAN countries — Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam, Myanmar, Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, and their largest trading partners which comprise of Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea.

However, since India has opted out of the agreement, the RCEP would now have only 15 member countries that are expected to ink the agreement in early 2020.

Well, what really made India’s inclusion in RCEP that winning monopoly deal?

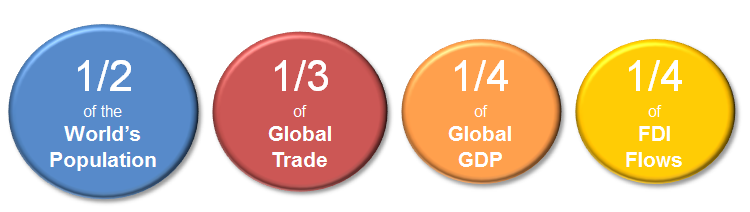

i. The 16-member deal i.e. an RCEP with India would be Asia’s largest trade agreement and would have accounted for more than:

ii. It would be home to a heterogeneous set of economies with a handful of commodity rich, resource poor, large along with small – and a blend of high, middle and low income economies.

iii. The RCEP would help to insure its member countries against isolationism and protectionist policies adopted by countries like the US.

iv. The RCEP would help make Asia the world’s factory by providing access to global supply chains and realising economies of scale.

v. The RCEP would promote easier FDI flows and technology transfers by multinational corporations.

While the RCEP looked like a strong deal, what gave India the bargaining power – the ownership of that coveted Property in the game?

A lot of substance to the agreement was due to India’s inclusion! India’s economy opens numerous doors for the other members of the RCEP.

i. Demographic advantage: It gives access to India’s 1.4 billion population with a huge youth consumer base whose incomes are increasing at 6-8% over the last few years.

ii. Uncompetitive domestic industry: India’s domestic industry is weak in terms of low productivity, inefficient processes and poor supply chains and hence would be an easy target for foreign competition.

India, which aims to be a 5 trillion-dollar economy by 2024-25 (as per PM Modi’s vision) driven by consumption demand with low domestic industrial competition, presents a hunting ground like no other RCEP economy does! Hence, it was in the best interest for all the member nations to have India ink the agreement. Without India, the deal loses a lot of it’s charm! – Doesn’t that give India some heavy leverage ?

India’s decision of not parting with its Dark Blue property i.e. not joining the RCEP agreement was because its “issues and concern” were not satisfactorily addressed. What were the major concerns that India sought resolutions for?

i. Trade Deficit: The most pressing concern that India faces with signing the agreement is the risk of running into wider trade deficits! These concerns are not unwarranted given India’s huge trade deficit with China. China is India’s largest trading partner while we are merely their 11th largest. India had a trade deficit of $104 billion with all RCEP countries put together. More than half of this was with China alone standing at $53 billion. This has raised worries about India being flooded with Chinese goods once the dreaded deal takes effect.

ii. Tariff reductions that would eventually impact domestic industry: The RCEP deal format required India to abolish tariffs on more than 70% of goods from China, Australia and New Zealand, and nearly 90% goods from Japan, South Korea and ASEAN. This would have made imports to India, cheaper. The domestic industry would have had to level up multiple times to match the quality and price of imports. If the domestic industry would have failed to do that, consumers would readily shift to imported products leaving the already fragile domestic industry in doldrums.

There was a fear that there would be a surge in dumping of cheaper goods such as electronic items, organic chemicals, especially from China on one hand and of dairy and farm products from Australia and New Zealand on the other.

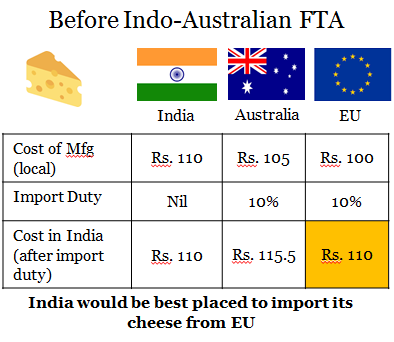

This can be explained by a simple example, say, of manufactured cheese.

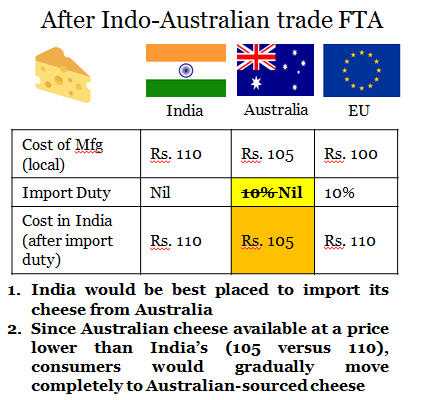

Consider 3 trading entities – India, Australia and the European Union (‘EU’) – each manufacturing cheese at different price points per kg. (say 110, 105 and 100, respectively).

Before a possible Indo-Australia FTA, the import duty on cheese would be, let’s say 10%; which meant that landed price in India of EU cheese would be 110 and Australian cheese was 115.5, respectively. Post an Indo-Australia FTA, which eliminates import duty on Australia, the landed price changes to 105 for Australia and 110 from the EU.

Consequently, India would divert all its imports of cheese from the EU to Australia, even though EU is a lower cost source. Further, with Australian cheese available at a price point lower than India’s (105 versus 110), consumers would gradually shift to Australian-sourced cheese – thereby creating trade where none existed and shutting down large numbers of Indian factories making cheese.

While the example is purely illustrative, it isn’t entirely hypothetical. Post the RCEP pull out, Amul’s iconic ad-strip showed the Amul girl leading a farmer couple carrying milk-buckets with the punchline – “Firm PM, Farm PM”.

iii. Pact seen to undermine the “Make in India” initiative: There are serious concerns that regional trade agreements like the RCEP need not always be beneficial from the “Make in India” perspective. While “Make in India” is the flagship project to attract foreign investment, this was never conceived of at the cost of domestic industry. Even after more than a quarter of a century of economic reforms, Indian manufacturing is yet to mature to be competitive enough to face the vagaries brought about by international trade.

What were the contentions that India raised but were not accepted by the RCEP members?

i. Tariffs on goods: Several members have requested that import tariffs on agricultural and industrial goods be eliminated for more than 90% of tariff lines. This implies gradually phasing out tariffs in India and exposing both agriculture as well as industry to severe competition from RCEP members.

Australia and New Zealand have demanded that India lower tariffs on dairy and wheat in particular and that tariff elimination should occur on items of significant trade value rather than just a large number of items.

The major concern for India is virtually free goods trade with China, where cheap imports are thought to have adversely affected import, substituting manufacturing sectors in India. Due to pervasive state-subsidies, Chinese firms have prices that only a few Indian firms can match.

India’s first Offer: Tariff elimination based on a three-tier system with 42.5% of tariff lines for China, Australia and New Zealand, 65% for Japan and Korea and 80% for ASEAN.

Rejected! Other RCEP members were in favour of a single offer for all RCEP members.

India’s second Offer: Despite fierce opposition from its farmers and industrialists, India made a new offer of eliminating tariffs on 70-75% of goods with some deviations for China, Australia and New Zealand which are not FTA partners.

Rejected! As this did not satisfy other RCEP members, particularly Australia and New Zealand which were insisting on increased market access for their dairy and wheat. Agriculture remains a difficult area for RCEP negotiations as India wishes to protect the livelihoods of the rural poor who are electorally important.

ii. Tariffs on services: The RCEP offers inroads for Indian services to China and the rest of East Asia, where India has achieved a comparative advantage on world markets. These advantages include information technology, professional services, law, banking, and educational services. Moreover, India has seen increased tourism arrivals from the Asia-Pacific region, and tourism services offer further opportunities for Indian businesses.

India demanded services trade liberalization in return for opening up of goods trade in the RCEP negotiations.

India’s Offer: Easing visa restrictions on the movement of skilled workers across RCEP borders for short-term work. Emulating the APEC Business Travel Card, it had proposed an RCEP Travel Card to facilitate visa-free travel for movement of skilled workers in areas such as information technology, engineering, training and investment banking.

Rejected! There were only a few offers from RCEP members in this area. ASEAN members have refused to offer even a limited level of openness that exists among the ten members of the grouping. ASEAN members are concerned that temporary movement of Indian skilled workers could become permanent with a loss of local jobs.

The other issues that India did not get a favourable for were as follows:

iii. India wanted an auto-trigger mechanism to be institutionalised in the pact. This would serve as a protective mechanism that any member country could invoke to safeguard against sudden and significant surge in imports after RCEP came into effect.

iv. India wants exemptions built into the ratchet obligations. A ratchet obligation implies that a member country cannot raise tariffs once the pact comes into effect. An exemption would imply that a country will be able to erect restrictive measures later on grounds of protecting their national interest.

v. There was also the issue of data localisation under the RCEP. India wants all countries to have the rights to protect their data. This would imply that countries would share data only where it is “necessary to achieve a legitimate public policy objective” or “necessary in the country’s opinion, for the protection of its essential security interests or national interests”

vi. Another key issue was the “base year”. India was opposed to the proposal that 2014 be treated as the base year for reducing tariffs, effectively implying that member countries should slash import duties on products to the level that existed in 2014. India was trying to push for 2019 as the base year, given that import duties on many products such as textiles and the electronic products have gone up in the last six years.

Since India’s grievances were not satisfactorily answered by the negotiations made at the Bangkok summit, it decided to pull out of the agreement. This offers lessons in foreign policy as much as it does in the trade domain.

On one hand, we should not go back to the old dogmas of economic independence and import substitution. While on the other, embracing the new dogma of globalisation without a cost-benefit analysis would be equally dangerous.

Has India made a winning deal by not parting with its Dark Blue properties i.e. by opting out of the RCEP agreement?

Opting out of RCEP means India will have to rely on multiple bilateral trade agreements with other nations to ensure that its exporters have market access.

An economist says that given India’s size, its exit from the RCEP would greatly reduce its (RCEP’s) coverage and significance. Although India may lose market access to Asian economies at preferential rates, its vulnerable domestic industries would be protected from intense competition and more importantly, Chinese dumping.

In short, in this ongoing battle of fixing the severe domestic demand slump, India chose not to further hurt the competitiveness of its local industries. This should come as a relief, as this certainly would have not been an opportune time for India to enter into this agreement with its ailing domestic economy.

Follow Us @