With the tech savvy Gen Z coming of age and entering the workforce, the demand for cheap and efficient services “on the go” have witnessed stupendous growth. The need for cab rides, grocery deliveries and at-home services at just a click of a button has paved the way for the infamous gig economy to hit it big. It ought not to come as a surprise that this industry is among the few that has weathered the pandemic and if I may daresay, has emerged stronger. The definition of gig has expanded to include workers of all kinds – ranging from teachers to coders to delivery persons. You name it, gig’s been there.

A Brief History Class

Since 2009, the term “gig economy” has been used to refer to part-time or freelance-based work, often connecting with customers through the web. However, most millennials are familiar with associating “gigs” to their college-day musical ventures. So, how did gigs really come to be?

The millennials seem to have it right, for the term gig was coined in the early 1900s to refer to performances by Jazz musicians. Gig work as we know it today, though, premiered with the Great Depression in the 1930s which had forced several farmers to sell their land and work as migrants, moving from farm to farm to find work. A decade down the line witnessed the onset of Temp Agencies – staffing agencies that connected employers with temporary workers. This was more prevalent in industries such as typing services, call centers etc. Even in the 1990s, only as much as 10% of Americans worked in alternative employment.

Needless to say, the digital age escorted the gig work to a magic broomstick and sent it shooting to the stars. Craigslist was the first of its kind, transforming from an Events Newsletter to a classified advertisement with sections devoted to jobs (especially gig work), followed by UpWork in 1999 (which to this day remains the largest global freelancing website) and Fiverr in 2010. By this time, people were getting used to the idea of side hustles and even quitting their day jobs to take to pursue full time gig work. Your modern-day YouTuber is a prime example of the same.

The concept of gig as an economy emerged with the rise of apps like Uber who operate worldwide as an on-demand driving platform. As mentioned, the gig economy promised efficiency, but at a cost. The workers weren’t given enough. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Part-time work: Torrid before COVID?

Prior to the pandemic, the gig economy was gaining momentum on account of the flexibility it offered its participants. Further, it allowed people to beta test a potential career path. Consider an accountant who wishes to get into marketing. While this might’ve been a tough bet for him to convince his new employers to take on earlier, now he is presented with an alternative. He could continue being an accountant during the weekdays and work on developing his marketing clientele through Fiverr in the weekends. In a few months’ time, he’s a top seller on Fiverr. He quits his job and bags his dream marketing job almost immediately thanks to his gig work-ex.

But not everyone has a similar career trajectory. App-based service companies such as Ola, Uber, Zomato and Swiggy were found to have amongst the worst working conditions amongst Indian startups, according to a study led by Oxford University researchers. The only factor they abided by, it seems, was sticking to paying at least the local minimum wage. This can be accounted to gig workers being excluded from the labor code around the globe, including India (until quite recently), and this enabled many platforms to exclude them from provident funds, maternity leaves, sick leaves and work-related health benefits. Besides, the uncertainty of a regular paycheck left a lot of semi-skilled and unskilled workers scampering around to make a living.

Nevertheless, in 2018, 70% of corporates surveyed by a HR consultancy reported that they had used gig workers at least once.

The Magnetic Effects of the Pandemic

The global impact of the pandemic on the industry as a whole, however, remains fragmented and uneven. Recall how most of the gig workers before the onset of the pandemic came from the ride hailing industry? It isn’t shocking that around half of gig workers globally had lost their jobs (either due to lack of demand or because of suspended operations) and even those that were able to retain their work found themselves earning just two-thirds of their previous incomes on average. Governments around the world started doing what they do best and demanded a reform, so companies started offering sick pay to their gig workers… with an expiry date. The results differed by country and most often than not, these workers found themselves in a dilemma – Either go to work and risk getting ill or stay at home and face financial ruin. Even the skilled were made to face the brunt as more and more coders, writers and video editors joined online platforms, thus increasing competition and reducing price.

Drawing on both our personal experiences, though, it may not be hard to see how the picture painted thus far could be highly varied. Our behaviors have changed drastically over the past year- from going to the salon to calling masseuses home on Urban Clap, shifting from hospitals and vet clinics to online consultations through web aggregators and even trying our own hands at freelancing. Those laid off from the workforce were able to find alternative freelance work on the web. Even your neighbor’s preteen is making money off of YouTube.

Alas, though, for the rules of economics go as follows:

i. Lower demand undermines the price, and

ii. Higher supply undermines the price.

In this sense, however, there is a uniting (albeit distressing) factor that unites the gig economy.

A Surety of Social Security?

It seems like we’re getting there. With platforms refusing to improve contractual terms and denying responsibilities toward their workers, worker unions have initiated legal actions in countries such as the US and UK. Meanwhile, platforms fight to stay their claims that their workers are but contractual based temporary employees.

In the backdrop of all this drama, the Indian Parliament has taken on a first mover advantage (of sorts) by passing new labor laws that recognize gig workers as new occupational categories. Companies have been asked to contribute 1-2% of their annual turnover or 5% of the wages to gig workers, whichever is lower, as part of a social security scheme. Now on, platform workers in India would be eligible for features such as insurance cover, maternity leaves, provident funds and much more. The code also mandates a maximum of an 8-hour workday and a 6 day workweek, and also specifies overtime rates (can we just start calling them gig employees from now on?).

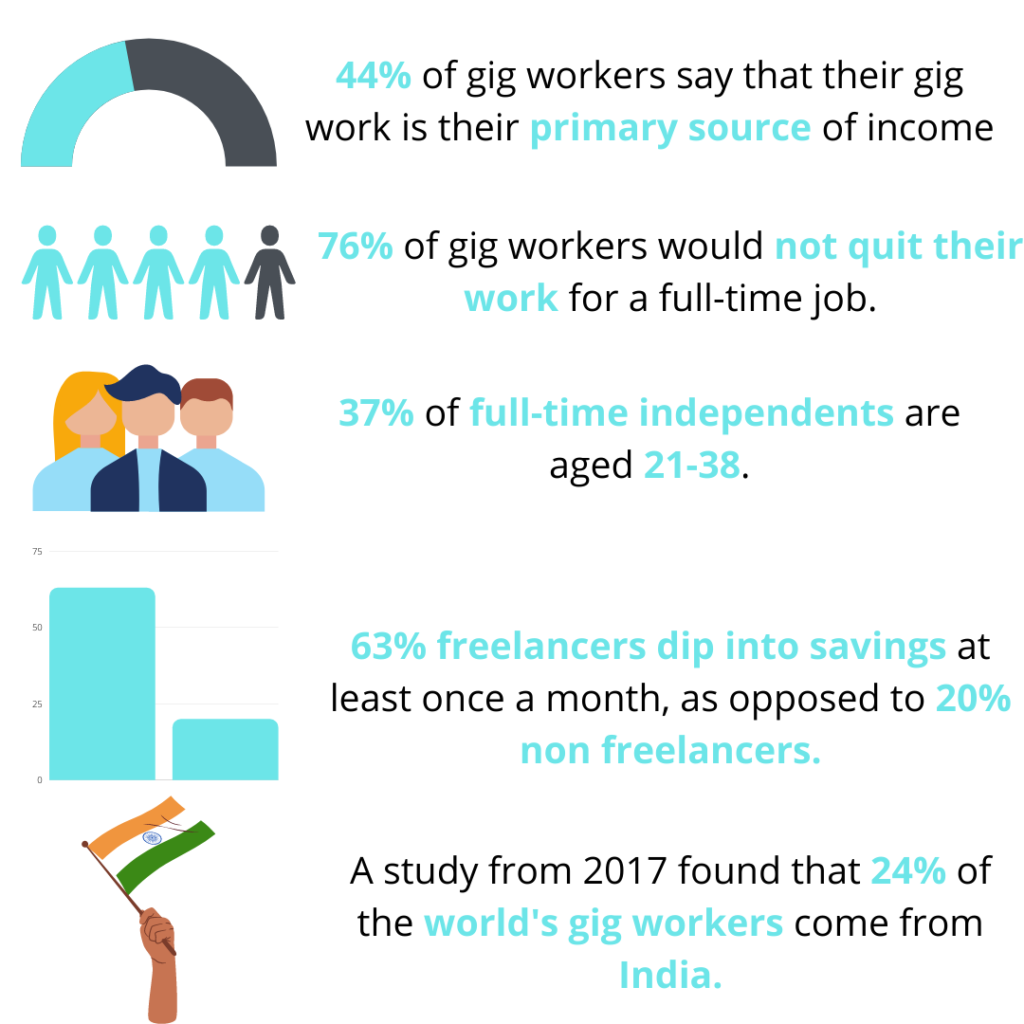

No wonder India has been ranked amongst the top 10 countries of the world in the Global Gig Economy Index Report, which observed freelance workers in India rise from 11% in 2018 to a stunning 52% in 2019.

Woo hoo or Boo hoo?

Yet, Indian gig workers continue to protest. Take the example of Swiggy, where the base pay of delivery persons was reduced from Rs35 to Rs 10 per delivery! This found the All India Gig Workers Union raising banners and protesting. But… what about the new labor laws?

You see, the labor law is hidden with a layer of deficiencies. Gig workers can only claim benefits provided under the Code of Social Security (the labor laws dedicated specifically to them) but are unable to claim other labor rights. For some eerie reason, they’re also not allowed to go to court for better and stable pay.

A walk down memory lane

It wasn’t too many decades ago that factory workers were pushed under the rug but emerged in the form of unions and claimed the rights that they deserved. It is but a matter of a few months or years before the gig economy witnesses a similar shift.

With 4 in 5 millennials and Gen Zers preferring gig works to 9 to 5 jobs, and with more and more day jobs moving onto a permanent WFH style which blurs the gap between the two, the industry is set to rumble sooner rather than later. 73% of Gen Zers have already engaged in the gig economy by choice, earning incomes even while in school. Unless large scale employment programs are launched by the government, the gig economy will undoubtedly emerge as an ever-pervasive sector. It still remains for us to figure out if such a fragmented sector could ever be regulated with uniform laws across platforms, but one thing’s for certain. Gig is definitely going big!

PS. Remember that study conducted by the Oxford University researchers? According to their report (Fairwork India Ratings 2020), “While Swiggy, Zomato and Uber scored 1 out 10, Ola, Housejoy, BigBasket and Amazon scored 2 out of 10. Grofers and Dunzo managed to score 4, Flipkart at 7 and Urban Company ranked at the top with a score of 8 out of 10.” Quick question. Does quitting your job and working as a freelance masseuse sound appealing to you now?

It may also be worthwhile to note that this article is brought to you by the gig workers of The Financial Pandora, who wish to spur up conversations with you about industries, economy, business and finance 🙂

This post was written in collaboration with Asif Yahiya Sukri LLP. Asif Yahiya Sukri LLP provides unparalleled personalized financial services to a broad range of clients across different geographical locations. With a presence in the USA, India and the MENA region, they ensure that all of your financial decisions are made carefully and with your best interests in mind. They are innovators who understand what goes into building companies.

You can also reach out to them on info@aysasia.com

Follow Us @

First they quit their full time jobs to work as gig workers so that they are not bound by work structure and clearly defined deliverables. Then when life start going south, they mobilise social media to paint a picture of exploitation…. Then they start demanding insurance cover, maternity leaves, provident funds and much more (which they had in the first place when they also had to commit to deliverables).

Millennials, GenX,Y,Z.. need to understand this simple rule – it’s a world based on ‘give’ and ‘take’, in that order.