In 2019, A textbook titled Macroeconomics, written by three MMT proponents: William Mitchell and Martin Watts (both of University of Newcastle, Australia) and L. Randall Wray (Bard College) was published by the Red Globe Press.

This Newsletter is being written with the aim to dive into the MMT policy and make our readers understand and think for themselves if they subscribe to this theory. As I studied MMT from various textbooks and sources and spoke to Economists at UBS and Goldman Sachs, I was often puzzled about what precisely was being asserted.

Over the past year or so, much media attention has focused on a new approach to macroeconomics, dubbed Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) by its proponents.

The rise of MMT occurred in a rather unusual way. From its name, one might guess that it was at top universities that this theory was worked on, as prominent scholars debated the fine points of macroeconomic theory.

But that is not the case., MMT was actually developed in a small corner of academia and became famous only when some high-profile politicians particularly Senator Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a representative drew attention to it because MMT conformed to their policy views.

MMT begins with the government budget constraint under a system of fiat money.

“Fiat money is a government-issued currency that isn’t backed by a commodity such as gold. Fiat money gives central banks greater control over the economy because they can control how much money is printed. Most modern paper currencies, such as the U.S. dollar, are fiat currencies.”

According to Mitchell, Wray, and Watts the standard approach ( Which has been followed up until now), which relates the present value of tax revenue to the present value of government spending and the government debt, is misleading.

They write, “The most important conclusion reached by MMT is that the issuer of a currency faces no financial constraints. Put simply, a country that issues its own currency can never run out and can never become insolvent in its own currency. It can make all payments as they come due.” ( Something we’d love to have, wouldn’t we? ).

“ Ah, give me a minute. Let me just go print some money to pay for this samosa “

As a result, “for most governments, there is no default risk on government debt.”

To be sure, a currency-issuing government can always print more money when a bill comes due. That ability might seem to release the government from any financial constraints because of the assumption that money can be printed to take care of liabilities.

Certainly, if an individual were granted access to the monetary printing press, his or her financial constraints would become much less binding. But I am reluctant to reach a similar conclusion for a national government, for three reasons.

First, in our current monetary system with interest paid on reserves, any money the government prints to pay a bill will likely end up in the banking system as reserves, and the government (via the Central Bank) will need to pay interest on those reserves. That is, when the government prints money to pay a bill, it is, in effect, borrowing. The money can stay as reserves forever, but interest accrues over time.

An MMT proponent will point out that the interest can be paid by printing yet more money. But the ever-expanding monetary base will have further ramifications. Aggregate demand will increase due to a wealth effect, eventually spurring inflation.

Second, if sufficient interest is not paid on reserves, the expansion in the monetary base will increase bank lending and the money supply. Interest rates must then fall to induce people to hold the expanded money supply, again putting upward pressure on aggregate demand and inflation.

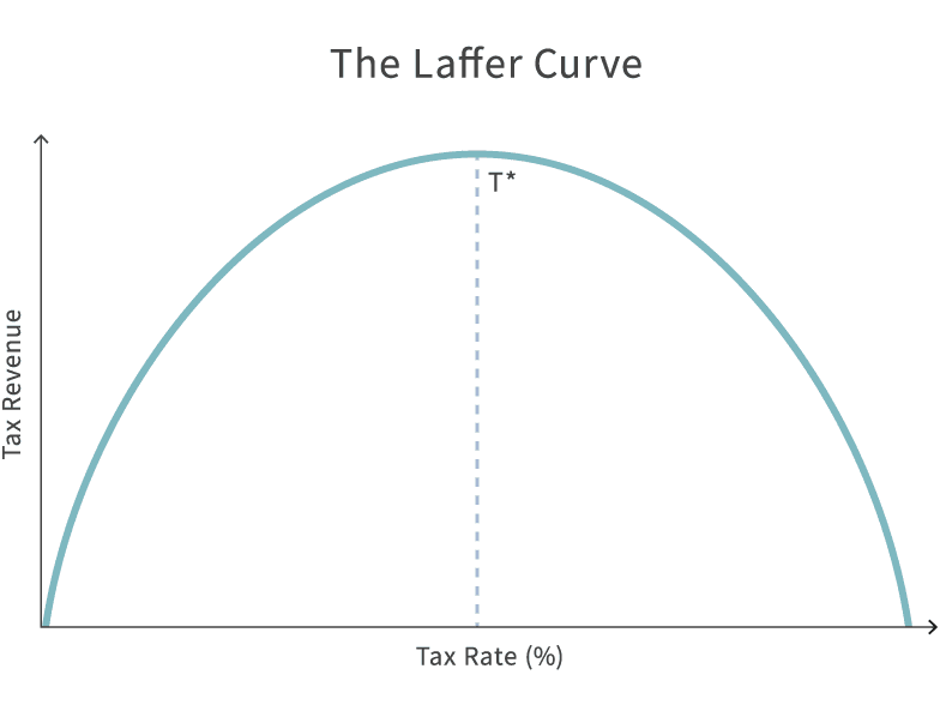

Third, the increase in inflation reduces the real quantity of money demanded. This fall in real money balances, in turn, reduces the real resources that the government can claim via money creation. Indeed, there is likely a Laffer curve for seigniorage.

“The Laffer Curve is a theory developed by supply-side economist Arthur Laffer to show the relationship between tax rates and the amount of tax revenue collected by governments. The curve is used to illustrate Laffer’s argument that sometimes cutting tax rates can increase total tax revenue. ”

A government that acts as if it has no financial constraints may quickly find itself on the wrong side of this Laffer curve, where the ability to print money has little value at the margin. Faced with these circumstances, a government may decide that defaulting on its debts is the best option, despite its ability to create more money. That is, government default may occur not because it is inevitable but because it is preferable to hyperinflation.

This brings us to the theory of inflation. If you subscribe to the mainstream view, you’re in for some confusion or amusement depending on how well you understand economics, the mainstream view explained most simply by the quantity theory of money, that a high rate of money creation is inflationary. Proponents of MMT question that conclusion. They assert that “no simple proportionate relationship exists between rises in the money supply and rises in the general price level.”

This assertion overstates the case against the mainstream view.

Mainstream macroeconomists also go beyond the most simplistic quantity theoretic reasoning. It has been stressed that money demand can be unstable, that distinguishing monetary and nonmonetary assets is difficult in a world of rapid financial innovation, that expected future money growth can influence current inflation when people are forward-looking, and that various factors beyond monetary policy influence aggregate demand and inflation. They also acknowledge that, under current policy arrangements, central banks target interest rates in the short run and inflation in the longer run and that monetary aggregates play a small role in achieving this.

But these ideas refine the quantity theory of money rather than refute it. MMT proponents advance a very different approach to inflation. They write, “Conflict theory situates the problem of inflation as being intrinsic to the power relations between workers and capital (class conflict), which are mediated by government within a capitalist system.”

It might seem Bogus but it does sound interesting.

That is, inflation gets out of control when workers and capitalists each struggle to claim a larger share of national income. According to this view, incomes policies, such as government guidelines for wages and prices, are a solution to high inflation. MMT advocates see these guidelines, and even government controls on wages and prices, as a kind of arbitration in the ongoing class struggle. Mainstream theories of inflation emphasize not class struggle but excessive growth in aggregate demand, often due to monetary policy. This idea also appears in MMT. Its proponents admit that “all spending (private or public) is inflationary if it drives nominal aggregate demand above the real capacity of the economy to absorb it.”

The advocates of MMT, however, make this possibility seem more hypothetical than real. We are also told that “capitalist economies are rarely at full employment. Since economies typically operate with spare productive capacity and often with high rates of unemployment, it is hard to maintain the view that there is no scope for firms to expand real output when there is an increase in nominal aggregate demand.” At the risk of seeming like the boy with the hammer who thinks everything is a nail, let me connect this observation from MMT with mainstream new Keynesian research.

Let’s first recall the work on general disequilibrium from the 1970s. (Barro and Grossman, 1971; Malinvaud, 1977) These theories took wages and prices as given and aimed to understand the allocation of resources when markets failed to clear.

According to these theories, the economy can find itself in one of several regimes, depending on which markets are experiencing excess supply and which markets are experiencing excess demand. The most interesting regime is the so-called “Keynesian regime” in which both the goods market and the labour market exhibit excess supply.

In the Keynesian regime, unemployment arises because labour demand is insufficient to ensure full employment at prevailing wages; the demand for labour is low because firms cannot sell all they want at prevailing prices; and the demand for firms’ output is inadequate because many customers are unemployed. Recessions result from a vicious circle of insufficient demand. Now fast forward to the next decade. Because so much of the Keynesian tradition assumed that wages and prices fail to clear markets, subsequent new Keynesian research, mostly during the 1980s, aimed to explain wage and price adjustment. This literature explored various hypotheses: that firms with market power face many costs when changing prices; that firms pay their workers efficiency wages above the market-clearing level to promote worker productivity; that wage and price setters deviate from perfect rationality; and that there are complementarities between real and nominal rigidities. (Yellen, 1984; Mankiw, 1985; Akerlof and Yellen, 1985; Blanchard and Kiyotaki, 1987; Ball and Romer, 1990).

There is an important but often neglected relationship between these two lines of new Keynesian research. In particular, one can view the later work on wage and price setting as establishing the centrality of the Keynesian regime highlighted in the earlier disequilibrium research. When firms have market power, they charge prices above marginal cost, so they always want to sell more at prevailing prices. In a sense, if most firms have some degree of market power, then goods markets are typically in a state of excess supply. This theory of the goods market is often married to a theory of the labour market with above-equilibrium wages, such as the efficiency-wage model. As a result, the Keynesian regime of generalized excess supply is not just one possible outcome for the economy, but the typical one. This logic brings me back to MMT. The conclusion that “economies typically operate with spare productive capacity” can be interpreted as meaning that economies are usually in the Keynesian regime of generalized excess supply.

In that sense, MMT is akin to new Keynesian analysis. At this point, it is worth distinguishing the natural level of output and employment from the optimal level. The natural level is the level where the economy finds itself on average and toward which the economy gravitates in the long run, whereas the optimal level is the level that maximizes social welfare. When generalized excess supply is the norm due to pervasive market power, the natural level is below the optimal level. Inflation tends to rise when output and employment exceed their natural levels, even if they remain below their optimal levels. After all, price setters do not aim to maximize social welfare. They aim to maximize private welfare, and they do so by hitting their target mark-ups of prices over marginal cost.

Here is where MMT economists diverge from new Keynesians. An MMT economist might say that policymakers should aim for the optimum. If price setters are thwarting that goal by raising prices, policymakers can fix that problem by using price guidelines or price controls.

A new Keynesian would admit that, in a world of pervasive market power, private price setting is not first-best. But while getting the government involved in price setting might improve the allocation of resources from the standpoint of simple theory, the complexity of the economy and the history of price controls suggest that this solution is not practical. In the end, my study of MMT led me to find some common ground with its proponents without drawing all the radical inferences they do. I agree that the government can always print money to pay its bills. But that fact does not free the government from its intertemporal budget constraint. I agree that the economy normally operates with excess capacity, in the sense that the economy’s output often falls short of its optimum. But that conclusion does not mean that policymakers only rarely need to worry about inflationary pressures. I agree that, in a world of pervasive market power, government price setting might improve private price setting as a matter of economic theory. But that deduction does not imply that actual governments in actual economies can increase welfare by inserting themselves extensively in the price-setting process.

“Put simply, MMT contains some kernels of truth, but its most novel policy prescriptions do not follow cogently from its premises. “

Welcome to our Newsletter on Economics, here we talk about ground breaking ideas and developments in the land of Adam Smith, Alfred Marshall, JM Keynes, George Soros, Robert Shiller and other Economists. We aim to please which is why our newsletters are written in the laymen’s language.

Stay tuned for our next newsletter: The Economics of Innovation.

Follow Us @